![]()

CHAPTER TWENTY NINE

14 of Marpenoth 1371, Year of the Unstrung Harp

“A remarkable claim - is it now my turn to cry foul play and throw wild accusations?” At least that was what I wanted to say, but I could not. My tongue went numb inside my mouth, fragile and erratic thoughts clinked inside my head like a handful of glass marbles inside a leather sack that a child might carry to keep her treasures safe.Bright fragments of images, sounds, and smells cascaded through my mind in a virtual kaleidoscope of patterns. I saw myself rolling into a ravine overgrown with blackthorn after punishing Farheed with magic on the night of my departure from Amkethran; then Omwo’s face scrunched in agony as my spell hit him between the eyes - and the taste of my own bile as I collapsed on the dirty floor of Zaureen’s audience chamber right after that. I remembered Chyil’s speculations about the source of the nightmares that I had suffered with increasing intensity after I had begun exploring my magical talent. According to him, those vicious dreams were the product of my own mind set upon self-destruction and self-punishment. But what else could one expect from an elderly priest, half-senile, and obsessed with the idea of universal clemency?

Naturally, I had dismissed his speculations as pure lunacy. Before my meeting with the dragon, I had thought my fits of sickness were the side effects of the catastrophe that had been orchestrated by my enemies, and that had originally cost me my memory. After Adalon’s scrying I could not continue to deny the truth: someone had set a barrier between me and my magic, and presumably the caster of the geas was way too powerful for me to tackle his ‘gift’. The one manifestation of my latent ability when I destroyed a piece of dinnerware using an incredibly high level magic did not count, since I had no control over that ‘hidden potential’. Besides, disintegrating a soup bowl was not exactly the same as dismantling the geas, and I would not have known how to proceed with that dubious task even if I had the power.

In all likelihood, the spell had been forced on me by the Seldarine - who else but the elven gods would have had the power to make it look like the weaving was done by none other than myself? The implications were dire, and the only way I could hope to appease the divine meddlers was to continue to play the game by their rules. Maybe my loss of memory was also part of the Seldarine’s plot? Corellon’s symbol passed to me by the water elemental was a telling sign. Now that Adalon had told me the deity’s name the nature of the silver crescent became transparently clear. Looking back, it was almost frightening to realize that I had never questioned the fact of my sudden knowledge. I had simply admitted my recognition of Corellon Larethian and his portfolio, as if paging through the blank book of my memories I had noticed nonchalantly that one page was not white anymore. Perhaps it was one of the attributes of the holy symbol, or perhaps the head of the Seldarine had chosen that ‘subtle’ approach to enforce his will, and make it clear that refusing the quest for Evereska’s salvation was not an option? Then again, it was quite absurd to think that the deity of High Magic and mages might need my help to save the elven city, (which was probably under his personal protection), from the impending disaster. If he was concerned with the fate of Evereska – why would he rely on the compliance of someone as untrustworthy as me?

Was I not (according to Aluril) a convicted criminal pardoned at the eleventh hour but deprived of the connection to the Elven Spirit, and forever banned from the People’s society? Surely that was not a record befitting a god’s messenger! But if the future of Evereska was not really under threat, what was it that the head of the Seldarine really wanted from me but to test my compliance? Most likely, Corellon Larethian had thousands of devoted mages of all ages and levels to pick and choose from. Why would he stoop to use me, a lowly apprentice whose magical talent was a faint shadow of its former self, unless he was planning to unleash my full potential in some remote future? Through the geas he had made it safe to use me as his personal pawn in the game of divine chess. The thought of being reduced to the state of a divine puppet culled of any ability to cause ‘mischief’ was intolerable. I wanted to howl in anger and frustration. Yet, I could sense the dragon’s presence lurking over my mental shoulder and that, perhaps, saved me from the final humiliation of falling apart under her scrutinizing eye.

“I trust you are done rummaging through my mind?” My voice sounded hollow and remote even to myself. “Do you still think I was lying to you, or are you quite satisfied with your investigation?”

“You sound bitter, Exile, and something tells me that you do not believe a single word of what I said about your geas. Think what you want, I am not going to repeat myself. My strength is fading too quickly to maintain the level of attention needed to continue arguing with you. Casting the Mind Scan has cost me the last vestiges of my life-force. Know however, that I am not sorry. Even if I could have lived a thousand years more, as befits one of my race, I doubt I would have ever achieved a state of such contentment as I feel now. I do not have to kill you – and it means that my child will also live.”“Am I to presume that you will let me out of this hellhole alive?”

“Yes, my deceitful once-friend and betrayer of kin, I will let you go. Having looked into your mind, I know you cannot hurt my child – you have no means. It is ironic, but because of your geas I trust you more than I would trust a stranger in your place. There will be many that will seek my lair to partake of my hoard... and my daughter is too young to take care of herself. She will show you the way to the surface, but she has never been outside and might need your help to find the halfling village. You will take her there.”“You are correct. I have no desire to hurt the mewling chit, and if she can follow me out on her own I will not object.”

“For once your callousness is reassuring – I would be suspicious if you showed more zeal. It is settled then. The hin tribe should be able to take care of her needs, and when she is old enough she will find her way north and join her father’s clan.”A hoarse low hiss emerged from Adalon’s throat, as her scaly side rose and fell, causing tremor equivalent to a small earthquake. I almost fell down from my precarious perch on Iryklagathra’s back. The wyrmling, who had quietly followed me up, and was now curled in a ball at her original post by her mother’s side, responded with a desperate fit of chirruping.

“Miamla will follow you. Take her to the village and leave her in the care of their matriarch – Olphara is a friend, she will know what to do.”“Consider it done, Bright One. I am glad that common sense prevailed in the end. Alas, your thirst for vengeance was easier to sate than that of the Seldarine.”

“I gather you are still unhappy, even with the Seldarine’s second verdict? They were amazingly lenient that time in view of all your crimes. I have read enough of your mind to believe that you indeed don’t remember much. To forget all your great ambitions and your most cunning schemes… What a fate for a would-be god! Thinking of it, it is a better punishment than anything I would have done. Yet, you have dodged the sword of eternal damnation, and have blunted the edge of the Seldarine’s vengeance, with your honeyed tongue – I doubt not. Who knows what will become of you? Your fate is in your own hands. In memory of our past I won’t begrudge you your salvation... even though your treachery has cost me the life of my son, and the devastation of the city that was once the cradle of my youth.”“Spare me the preaching, Adalon. Submission is the fate of the weak - I would rather burn than be subjugated!”

At that point in our conversation, I was so vexed with Adalon’s taunting, that I completely missed the fact that her mental speech was fading and faltering with every phrase.

“Cease your ever stubborn display of arrogance... and don’t make me waste my dying breath laughing... you can be very accommodating when backed into a corner... just a while ago you begged and pleaded, and tried to bargain for your release, offering me your free will in exchange... and it turned out that it was not even yours to command...”“I did not plead! And even if I did... is there any pride in dying a senseless death?”

“Ultimately, you have procured your pardon... but you have paid with the tokens of humiliation and defeat... and a pledge of my daughter’s safety... for me that was worth more than your miserable life. Fear... the wrath of Suldanesselar and her Queen, Exile. Ellesime may not... be as accommodating... she may ask... for more...”The dragon’s voice was quickly fading from my mind, and I realized that she might expire before I had a chance to ask her any questions. Whatever she thought of her shallow victory - I still had a chance to defy the will of the elven gods later on, and at the moment obtaining information was more important than having the last word.

“That is the second time you have mentioned that name. I saw a... a woman who called herself Ellesime in my dream, but I did not recognize her face. Who is she?”

“...”

“Speak out, whilst you still can – I demand to know!”

“Ellesime is the Queen... of Suldanesselar... your... home city...”“Is that all? You cannot die on me before revealing at least something of my past! Answer me, I command you! What else can you tell me about Ellesime? Where can I find this Suldanesselar?”

“You command nothing, Joneleth. Not even your life. It... belongs... to the Queen... the one whom you betrayed in so many... ingenious ways... If you wish to make peace with your past... travel north. There... between the very edge of the Anauroch desert... and the Marsh of Chelimber... look for a wooded valley hidden among the Graycloack Hills... save Evereska and go... to the Forest of Tethyr... give her a chance to forgive you...”“Curse you, Adalon! Do not dare to depart now, not before I can ...”

“...let there be light...”

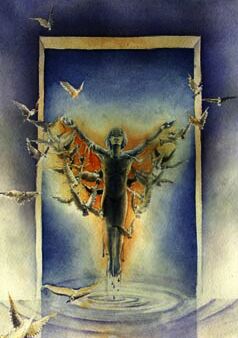

Adalon sighed deeply, trying to shift her giant head in her daughter’s direction a fraction, but failed at this final task. I glanced at the wyrmling – she was shaking violently from nose to the tip of her tail. A wave of tremors ran through the dragon’s dying body, and I saw a thin film of glaze cloud the surface of her fading eye. My last magic sphere, one of the consecutive three that I had had to summon that night, winked and died leaving us in the dark. The wyrmling wailed, almost like a human child, then went quiet. Then there was a strange motion in the air, as if a pair of ghostly wings brushed against my face as the dragon’s spirit freed itself from the mortal shell. At the same time, somewhere at a distance I heard the faintest of sounds – something akin to the ringing of a broken string on a concert violin. The warding spell collapsed. A jet of fresh air flowed into the stale atmosphere of the cave and stirred dust and debris, no doubt produced by the violent thrashing of the dragons’ bodies during their fight and through the agony of mortal throes. High above my head I saw the wide mouth of a tunnel previously concealed by the darkness; the fine dust dislodged by the gust of wind danced inside the column of light pouring from its heights.

When I shifted my gaze back to the dragon she was gone, and the stern rigor of death was quickly setting over her giant bulk. Adalon had not lied – she had removed the wards before succumbing to her wounds. I had entered the lair when the last rays of the setting sun were fading from the sky – could it be that our conversation had lasted all night? Judging by the sudden bout of exhaustion and weakness that hit me, it was quite possible.

I extended a slightly shaking hand, touching the dragon’s heavy eyelid. It was surprisingly easy to dislodge and I quickly pushed it over the milky surface of her dead orb, closing it forever. Adalon’s other eye had been blinded in the fight. Something pulled in my chest, leaving behind an unanticipated sensation of misery. It was odd. I tried to analyze my reaction at Adalon’s demise and failed. I did not exactly feel any relief – she was more of a nuisance than an enemy. I could not feel angry at her either, even though her untimely death deprived me of my answers. But I was certain that her last words would haunt me through the days to come: if you wish to make peace with your past... let there be light... they fell onto my ears like empty husks, devoid of any meaningful substance.

Every corporeal being polluting Toril with her breath was destined to die, be they valiant, cowardly, or neither, (although in my case I was set on putting off that unfortunate event for as long as possible). Yet Adalon had departed with a clear sense of relief. What was that supposed to mean - that forgiveness was sweeter than revenge? I wondered if that was the essence of her final speech. Her opinion hardly mattered now that she was dead, but the feeling of wretchedness would not go away – rather it wound around my heart like a cold viper, squeezing it gently in a slimy reel of coils.

Swearing under my breath, I climbed down Iryklagathra’s rigid paw and jumped onto the pile of bloody treasure. The dragonette followed in my steps, mewing like a small kitten.

“You there, yes I am talking to you – whatever your name is. It is time to depart, we don’t have all night!”

By that time, I was well adjusted to the telepathic communications of dragons; the ring from the Addazahr’s cache made the process easy, albeit I suspected that Adalon could have managed without it. I stopped and looked at the wyrmling expectantly, noticing for the first time the span and width of her wings. Judging by their size, Miamla, (I gathered that was Adalon’s pet name for her daughter, and decided to adopt it for it was easier on my tongue than her full name), should be capable of flying. Perchance, she was not as helpless as she looked?

“Can you fly, little one?” I asked in a slightly gentler tone. “We need to get out of here quick.”

The wyrmling stared back at me with an enigmatic expression, keeping her silence for many long minutes. There was something in her eyes, though, that instantly made me wish I had not been rude to her before - the eerie silence of the void that settles in after a soul has been deprived of its very last spark of hope. For what it was worth, the symptoms were all too familiar to me.

“Here girl,” I took a step in Miamla’s direction, stretching out a hand to pat her crested forehead.

The head of an adult silver dragon would have been graced with a pair of long slim horns, much resembling those of a gazelle. The wyrmling did not have the horns yet, only small bony protrusions behind the ears, but an ample silvery frill already ran down her neck and body, all the way to the tip of her sinuous tail. To my surprise, Miamla evaded my hand, moving sidewise with a quick grace natural in a lizard. But her vigor did not last long - after running a few paces her steps faltered, and she slumped onto the bed of coins no more than a few strides away from my feet.

“Remarkable stubbornness on your part,” I complained loudly. “What am I supposed to do now?”

I wanted to get angry at her but could not bring myself into the proper mood. The creature was too small to present any danger to me or be of interest as a potential ally, yet the heavy misery lodged in my chest would not let me dismiss her as a minor nuisance. There was also the matter of personal pride… or so I thought. Was I that spiteful and inconsistent? Breaking my promise to the dying dragon would feel like another form of defeat.

I gave the wyrmling an assessing look. All I could see from where I stood was the dragonette’s shivering back with a pair of frail wings folded rather like those of a large iridescent moth. Admittedly, it looked like the creature was crying, although I was not sure if dragons were capable of such displays. Adalon had never practiced this kind of behavior, at least not in the few short episodes of her life that I was aware of. I sighed, not daring to cross the distance between the two of us again, and realized with bitter clarity that I could not leave Miamla here any more than I could have refused Mirriam’s request to rescue her brother on that fateful morning in the desert. Something inside me was pushing me, making me act against my best reasoning. Was it another side effect of the geas? I really did not wish to know. Yet, what options did I have? The dragonette was too fast for me to capture and restrain. There was only one alternative - to convince her to follow.

“Will you listen to me, young one, or do you want me to go away and let you die at your mother’s side?” This time I spoke in Elven, since it had seemed to have had a soothing effect on her before.

No answer - the silver dragons seemed to be exceptionally good at the annoying trait of ignoring their vis-à-vis. I swore once again, and settled on the floor of the cavern, bracing myself for another long, heart-wrenching talk. Curse it! After the exceedingly taxing night, spent confronting Adalon, the last thing I wanted was a fresh argument with her daughter. On the other hand, it was not like I had to hurry now. There was absolutely nothing out there for me, worth rushing after it. As Adalon had smugly put it – I remembered nothing of my ambitions. Moreover, I was beginning to have serious doubts about my further course of action. My situation asked for long contemplation and reflection, and I knew that the moment I stepped out of the cave and rejoined my party, they would be all over me asking annoying questions and offering ridiculous advice, even if I managed to elude most of their inquiries and dodge the flurry of affection. The mere thought of what Mirri might do at our next meeting made me wince in discomfort, and I quickly shifted my eyes back to the little dragonette.

“Listen, I do not know how much of my conversation with your mother you understood, but would I be wasting my time on this charade if I wanted to harm you? All I have to do is leave you here to die.” I continued using Quenya, even though the wyrmling did not show any signs of reconciliation.

“You are not serious about this, are you? What is the point of avoiding me, when you are the one who will suffer the most? Or do you want to punish yourself for letting your mother die? There was nothing you could have done. There was nothing I could have done for her either, except maybe ease her anguish and give her some peace of mind. Which I believe I did, albeit unwillingly. I know a little about penance and self-punishment - it will not do you any good.”

I thought I discerned a slight twitching of Miamla’s tail that was out of pace with her violent shaking. Oddly enough, now I felt a need to talk to someone as well. After the sleepless night, the rhythm of my own voice was mesmerizing. I realized how badly I needed to distance myself from what had transpired between Adalon and me, to convince myself that there was nothing cowardly about wanting to live and restore my memories.

“Do you want to know how I came to be here?”

There was another jerking of the tail - this time more visible than the one before.

“Ah, you have heard me well enough, no need to pretend that you did not. You might recall some of the story that I told your mother, although I doubt you understood much of it. How well can you comprehend the spoken Common? Or maybe you can use draconic mental speech? No matter. There are things that run deeper than currents in the ocean, and things that are as bright and clear as the sun glinting on a polished mirror. It does not mean that simple things are not important, or that complicated reasons should be used to explain everything. Listen to me. The tale may be a tedious one to repeat, but it will teach you to strive for survival, and be happy with what little of yourself you can scavenge from the ruins of your former life.”

“There once lived someone who did not know who he was. All he could remember about himself was that one day he woke up in a strange place, among the strange people. They told him his name was Jon. But when he looked in the mirror he could not remember his face…”

As I went through my tale for the second time, I mused over how differently one would relay the same facts to a child, and wondered which version of the story would be the truer one. The Elven tongue gave my recital the ring of an epic, even though this time I omitted all the portents and the dreadful prophesies. Instead, I told Miamla about the elderly priest and his temple painted with the frescoes of Tethyrian merchants kneeling before Waukeen, all of whom (including the goddess) had the dusky complexion and sad dark eyes of true born Calimshites. I also told her about the small sheep wearing the tattered hood on its curly head, and the two youngsters dying from laughter on the roof. I talked about the noises inside the sandstorm, and why the grapes in Aluril’s oasis tasted like honey. I could sense Miamla’s mind through the ring on my finger, it was lurking behind the shield of her fear like a small fish that is drawn to the bright plane above, but is afraid of the shadows dancing on the surface. After I described the huge copper lantern that Omwo had strapped to his back when he had climbed down the slippery wall of the Naga’s lair, the wyrmling became caught in the story. I suppose Miamla’s vocabulary was not that good at the time, and she only understood five words out of ten, but the tale drew her thoughts away from her mother’s death, and that in itself was a blessing for her immature mind.

When I reached the point where we had had to be hauled up the wall in a big wicker basket, the dragonette finally raised her head and looked in my direction, settling into a sitting position on her hind legs. Her gaze was still shiny, and two wet streams ran down her small scaly face, but at least she was not shaking any more. I gave her an encouraging nod, and continued with my story without expressing any feelings on her obvious change of heart. After a while, I dared to give her another quick look, and stopped with an exclamation of utter astonishment – Miamla’s body was melting.

There is no other word to describe what was happening. I had seen Iryklagathra shapeshift into his dragon form from the human one before my very eyes; therefore I knew that dragons possessed this kind of magic. But I had never thought that a wyrmling so young could already assume her humanoid form. The dragonette maintained her fragile statuette-like appearance, but at the same time her limbs became slimmer and longer. She had lost her tail, and her claws shrank into her paws, to be replaced by delicate fingers with pink fingernails. The long column of her neck was reduced to a smaller humanoid version of itself. Her entire body was losing its lizard-like scaly texture and reshaping into the small naked form of an elven child no more than five winters old.

The most amazing transformation however was happening to her facial features. They lost their flat reptilian look as her nose became a daintily fashioned protrusion on a pale, cream-colored face that was perhaps a touch fey, but definitely pleasant to the eye. Her ears grew out of her skull and became elongated and pointy, even as the last remnants of her bony crest split into individual strands and then burst into a multitude of fine hair that draped her slim frame from head to toe in a veil of platinum-white locks. I could only gape at this astonishing performance. The fact that she had picked a prominently elven form for her humanoid alter-ego did not escape my notice. I had never seen another living being of my own species (not in this life anyway), and the wyrmling’s choice was flattering, if not entirely unexpected. She could have been my younger sibling, or my child – if not for the eyes that retained their silver color, and mesmerizing reptilian quality.

To say that I was stunned at her spectacular act was an understatement. Miamla’s choice of form clearly indicated her decision, but I was in equal measure pleased and disturbed at this new development. Surely, it could not mean that she had accepted me as a substitute parent? The child shivered and looked at me with an air of expectation – she was stark naked under all her hair, and although the air in the cave was not as cold as on the mountains’ slopes it was considerably draughty now that the magic barrier was removed. Judging by her immediate reaction, the wyrmling was not accustomed to her humanoid status and its implications, and now I was presented with a dilemma on how to remedy this. Not only the weather outside was freezing, having a female child in naught but her skin accompany me into the village was at best inappropriate. The hin tribe was a highly traditional and conservative community, and the girl, (although very small by elven and human standards), was almost as tall as an adult halfling.

“It would have been much easier on me if you had remained a dragon,” I complained loudly.

Miamla opened her mouth, but all she was able to produce were a few hisses and clicks, and she soon went silent again. The ring on my finger remained cold – perhaps it only worked on the dragons in their proper form, or perhaps she had not actively tried to project her thoughts.

“Do you even realize how many problems you will have in this shape?” I snapped in irritation, pacing up and down the small patch near the treasure pile crowned with draconic carcasses. “I suppose you don’t! Don’t even bother to respond. I will have to find you something to wear. Clothes – you know – things that you put over your skin to... to keep warm.”

The idea of explaining the notion of modesty to the dragon was a little weird, to say the least, and so I decided to leave Miamla’s social education to Olphara and her tribe. They would have all the fun of rearing the wyrmling anyway. To think of it, it might be easier for them to accept her in the village in her elven shape. And if she could sustain herself on normal humanoid food it would be even better. Perhaps her idea was not a bad one after all, I thought vaguely as I tried to find a solution to my new predicament. After some digging and sorting through the scalded and bloodied pieces of treasure, I finally selected a vest of dwarven chain mail. It was long enough to cover the child almost to her toes, although it left her neck and arms bare. But its metal gleam oddly matched her eerie appearance, and after I had convinced the wyrmling to put on the strange outfit I felt that she was pleased to have a second skin that was almost as good as her old one.

She went to her mother’s body one last time, and climbed on top of the grotesque mound of the dragon corpses, fast and nimble as a weasel even in her shiny metallic dress. There she stayed for no longer than a minute, clinging tightly to Adalon’s gleaming hide, and murmuring something in slurred Draconic. I did not try to listen, it was their private affair. My own mind struggled with an odd tangle of melancholy, bitterness and relief. The feeling was too complicated to express, yet almost palpable to my mental touch. I suddenly wished to be out of this gloomy and oppressive cavern, gleaming with treasure and stinking of violent death. And so we left the place that was once Adalon’s sleeping chamber but now has become her tomb, and followed the slope of the grand tunnel that led us into another cave that served as the lair’s entrance hall.

And there I stood in awe, for the grey dusk of the predawn had slipped away while we were talking, and the fierce orange ball had cleared the crimson jumble of clouds above the distant silhouette of the mountains, pouring a flood of liquid gold onto the world around us. The sunrays washed over my face triggering a feeling of déjà vu, as if another memory was trembling at the very edge of remembrance. Then it was lost in a warm wave of existential bliss. It felt like the most spectacular sunrise I have ever seen. I stopped for a moment, trying to imagine the slow agony of being buried alive that I had avoided, barely, and savoring a peculiar sensation of emotional reprieve that in some old medical manuscripts is sometimes called catharsis. The feeling in itself was so complex and excruciatingly sweet that I shivered in near physical pleasure at this newly discovered state. I knew that the misery of hesitation and stifled anger would catch up with me later on, but for the moment all I wanted to do was to stand there filling my lungs with the freezing mountain air, and enjoying the few fleeing seconds of suspense between yesterday and tomorrow.

Someone tugged at my sleeve. As I turned to Miamla, she caught my eyes with hers and after a brief hesitation shoved her small fist into my face. It was clutching a bright, silvery object. I cursed, but the girl only nodded and pushed Corellon’s crescent into my opened palm. As I stared at her in indecision, she vigorously shook her head and tried to put her lips into a shape that would produce the desired sound. That time it almost worked.

“Lle auta yessste,” she pointed down with her hand to confirm her intent.

And so I did.

![]()

Lle auta yeste’ - you go first (elv.)

![]()

| PREVIOUS CHAPTER |

|

NEXT CHAPTER |

![]()

Last modified on October 11, 2003

Copyright © 2003 by Janetta Bogatchenko. All rights reserved.

![]()